Renewed Beauty

A report from Andreas Rüfenacht und Barbara Bührer

Almost 500 years ago, the Wittenberg artist Lucas Cranach the Elder (1472-1553) painted the Madonna of the Grapes. It is natural for a painting of such considerable age to undergo age-related changes over the centuries. This created a craquelure – a network of fine cracks that widened into crater-like furrows as a result of repeated harsh interventions. Almost 100 years ago, these were covered with coarse, heavily darkened retouching, giving the Madonna of the Grapes an unsightly, spotty appearance.

For four months, the conservator Barbara Bührer removed the old retouching and heavily yellowed varnish - the protective layer over the painting surface. She then retouched the exposed damage. In this way, the Madonna of the Grape received the appreciation she deserved and her beauty can now be seen in its original splendour.

Ein Film von Linus Maurmann

Digital imaging and the scientific investigation

In order to match todays high standards of conservation, scientific analysis was carried out using digital imaging in the preparation for work. The different imaging technologies revealed the structure and state of preservation of the work. Removal of samples from the earlier retouching provided information about the substances used. These preliminary investigations served as the basis for the procedure and the careful selection of the methods and materials to be used. After expert discussion, the decision to proceed with conservation work on the painting was made together with the Peyer'schen Tobias Stimmer Foundation as the owner of the painting. The foundation funded the project.

High-resolution photography provided indispensable evidence before conservation started showing the appearance of the painting before restoration in visible light. The innumerable dark spots of the old, roughly applied retouching were particularly obvious on the skin areas, the so-called flesh tones. Small areas of damage in the paint layer revealed the panel's light-colored ground – for example on the cheek.

Oblique lighting makes plastic structures on the surface of the painting visible, such as the relief of the paint application (impasto) as well as later changes or damage. The oblique light photo shows the skill of the artist in modelling highlights in the Madonna's hair using thin, plastic lines. In addition to the ridges of craquelure edges, the brushstrokes of the old retouchings and breaks in the paint layer can be seen.

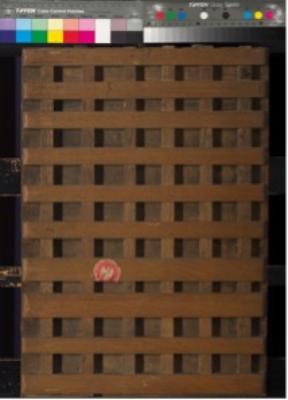

The original back of the painting is no longer recognisable. The horizontally grained beech wood panel was planed down to attach a supporting structure, a so-called 'tiling'. It should protect the panel from natural movement of the wood. Today we know that this conservation practise, which was common in the past, is mostly unnecessary and even damaging. Stickers, as well as inscriptions, numbers, seals or stamps, provide important information about the origin of a work of art.

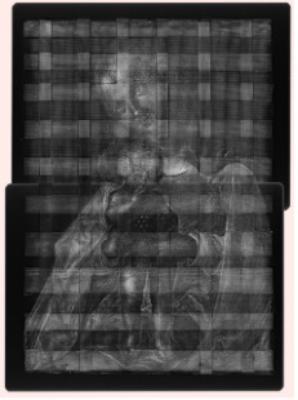

X-rays penetrate the layers of a painting. Radiation diagnostics is used in research to identify the process of creation, materials hidden deep in the structure, their treatment and condition. Painters used to use poisonous white lead for white tones. The lead content absorbs the X-rays to a large extent. Therefore, very bright areas of the recording show where the artist used this white.

Infrared radiation penetrates deeper into the image layers than visible light. In favourable cases, changes in the design or underdrawings can be recognised on a lighter painting ground. There are no underdrawings on the Madonna of the Grape. Possibly these coincided with the darker areas in the overlying painting – perhaps an indication of Cranach's routine workshop practise.

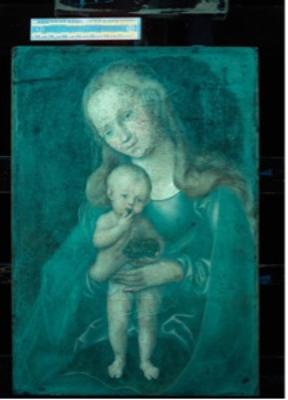

“Wrong” colors are assigned to the infrared image in digital post-processing. In this way, different materials such as color pigments can be recognized more clearly. Two frequently used blue pigments, lapis lazuli and azurite, can be easily distinguished using the false color technique: in the Madonna's cloak, the blue tones have taken on the same "wrong" colors. These are the same pigments. The absorption of infrared rays indicates azurite.

UV rays stimulate some substances on the surface of the picture to fluoresce. Depending on the nature and aging of varnishes and mediums, these fluorescences differ in brightness and color tones from yellowish green to dark violet. For example, retouches stand out darkly if they lie on a brightly fluorescent layer of varnish.

The photo taken after cleaning allows a look at the actual state of preservation of the picture. It serves as a record: compared to the previous and final state, it shows what was removed during the cleaning on the one hand and the extent of the retouching added on the other.

The many small damaged areas reach into the light primer. As devastating as they appear overall, the fine layers of painting have been preserved, even the finest eyelashes and hair are intact.